Jacob- People and training of gladiators

Gladiator Schools:

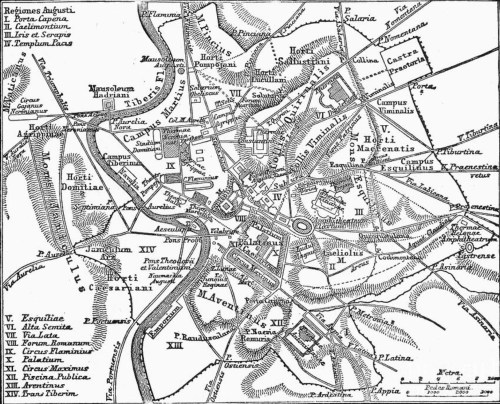

While there were many gladiator schools, by far the biggest and most important ones were the ones located right there in Rome. The first, Ludus Magnus, was the biggest; holding about 2,000 gladiators. Then there is Ludus Dacicus, east of the colosseum, used to train Dacian prisoners of the Dacian wars. Third is the Ludus Gallicus; the smallest of the gladiator school and more dedicated to training more heavily armoured classes. Lastly, the Ludus Matutinus; this school was more for beast hunters and not so much for gladiators fighting each other. The word matutinus means “of the morning” where these sorts of shows would be performed. The schools had their training ground in the middle, with their barracks and other supporting structures -such as a mess hall and a kitchen- surrounding the periphery of the training ground.

Where the Gladiators came from:

While there are many sources that suggest many different things about where the gladiators came from, there is a trend within the sources. The majority of the gladiators were criminals or slaves, but there were a few exceptions. There are accounts of volunteers who became gladiators professionally.

Employment of the gladiator schools:

The owners: Just like most corporate businesses today, the owners don’t do much except for accumulate money.

The Lanistae: The Lanistae can be assimilated to the managers of the ludus. What is interesting about the Lanistae, is that there seemed to have been a stigma with the lanistae and they were looked down upon; they were on the same ground as pimps and even the gladiators of that time. (Talbert, Slootjes, Brice. 133 )

Medici: The medici were the doctors of the Ludus. They insured that the gladiators’ health was kept up to par. They may have been slaves or prisoners, but the gladiators competing was a source of income for the owner of the ludus. Included with the medical care that the gladiators received, they also had access to decent food to keep their energy up. One account mentions that the gladiators ate barley water mixed with beans.. (Talbert, Slootjes, Brice. 126 )

Magistri: The magistri were the gladiators’ trainers. Most of the magistri was composed from retired gladiators, mostly because after retirement from gladiating, they did not have good prospects, so they trained newer gladiators. While the magistri were the official trainers, many of the gladiators helped each other out. The more experienced ones were in charge of training the newer gladiators, despite the fact that they may have to fight each other in the ring.

Training of the Gladiators:

The gladiators were separated in different ways. The first way they were separated was by social standing. The volunteers, or the professionals, were separated from the slaves and criminals and ended up getting better treatment. The slaves and criminals though, even though it wasn’t as bad as regular prison -they had to be healthy for fighting- it wasn’t up to par to the professionals. They were also separated based off of their fighting style, and each fighting style had their own trainer. It wasn’t unusual for the gladiators to befriend their fellow adversaries, because the friends usually were the ones that made their gravestone.(Coleman) Another point of segregation, usually the professionals went by their own name; while the slaves tended to have stage names that they used. One example is “Secundus” or “Lucky” (Talbert, Slootjes, Brice. 129)

In the arena:

Despite popular belief, there were actual rules when it came to gladiating; and it even included umpires. It wasn’t just kill your enemy, because you didn’t always have to. The gladiators were trained to fight with skill and accuracy; not necessarily to kill the enemy, but to disarm him or somehow disable him. (Talbert, Slootjes, Brice. 139)Remember, this is a show, even if it does seem like a battlefield. From there, it was decided by the crowd whether the defeated would die or be spared.

Among many things, one of the things that was harsh about the gladiating world is that you could have trained with someone, and even befriended him/her, only to be pitted against them in the arena. (Talbert, Slootjes, Brice. 137)

Special gladiator schools were created in Rome. Capua was one of them. Agents scoured the empire looking for gladiators to recruit, as their turnover time was very short.

History of the Games – Garrett

The games have roots in both religious funeral rites and practices created by the people located in modern day Italy. The Etruscans of Northern Italy held gladiator battles and chariot races as sacrifices to the gods. The Romans picked up the practice later and continued to hold the games about 10-12 times a year (Pierre). It was believed in Rome that when people died their souls would travel in human blood to the afterlife. Because this was a popular belief, they would kill slaves or prisoners of war at important funerals. At Julius Brutus’s funeral in 264 BC his family had 3 pairs of slaves fight each other to the death (ushitory.org). Other wealthy families followed this example and began having these fights as well to prove their wealth. People passing by would come watch these fights as well and someone eventually had the idea to put out chairs and charge people to come watch the fight. The funeral of P. Licinius Crassus 120 gladiators fought and his funeral took place over 3 days and ended with a massive banquet in his honor (Thomassen). This practice eventually changed from its religious routes to more of a political event to win the favor of the mob.

The games were originally created and funded to show one’s wealth at a funeral and ensure safe passage into the afterlife. This quickly changed once they realised that they could win the hearts of the poor and desolate masses by putting on these massive spectacles for free. Once the aristocrats realized that the games would slowly increase in size to become massive, almost unbelievable spectacles of bloodsport.

As with most entertainment industries the most important thing is to be bigger and better than your competition so each times gladiator games were put on they had to be better than the last. The first advancement in scope came when aristocrats began constructing wooden arenas filled with sand. Previously they had fought either out in the open or in a roped off area. With the sand there to absorb the blood that was spilled the games could be held more often and for longer periods of time. This increase in frequency and duration then allowed gladiators to become a big business. Gambling on the outcome of gladiatorial games became a massive industry with gladiators creating troupes or familia, with managers that would decide where and when they would fight. Schools that recruited slaves, criminals, and prisoners of war in order to teach them combat techniques. Some elite romans even owned their own troupes of gladiators. formed. This growth, backed by the most elite in Rome, lead to the games becoming massive spectacles lasting months at a time at the creation of dedicated arenas rather than improvised grounds.

But private citizens owning sometimes hundreds of well trained warriors was something that could not be ignored by the state. When the Roman Republic fell the Roman empire and the Senate assumed complete control over all gladiators. They also gave Roman courts the ability to sentence criminals to participate in the games. With the ever increase in popularity, amphitheatres made of stone were built to house the games. The first of these arenas was called the Amphitheater of Statilius Taurus and was built in 29 BC with the most famous of these, the Roman Colosseum being built in 80AD (Thomassen).

The history of using animals in the arena also have roots in funerals as well, with wealthy people would stock up native creatures to parade around in honor of the dead. They would teach these animals tricks as well as kill them in staged hunts called venationes. Wild animals first came into the games when elephants captured during the first punic war were taken the games in 252 B.C (ushitory.org). This really expanded however with the wealth figures of Pompey, Crassus, and Julius Caesar bringing in animals from Africa such as crocodiles, hippopotami, tigers, lions ,leopards, and more. Trajan’s games is famous for being the largest show ever put on. It lasted form 79-81 A.D and was held to celebrate his victory over the Dacians (ushitory.org). The games lasted 120-123 days and consisted of over 9,000 gladiators and about 11,000 animals (ushitory.org).These animal hunts were so popular that many Roman Emperors actually fought in these gladiatorial animal hunts in order to earn the honor that was afforded to to the coliseums greatest champions. Emperor Commodus is the biggest example of this as he is said to have participated in over 700 gladiatorial fights (Pierre).

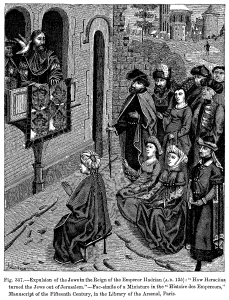

Eventually the attitude towards the games shifted dramatically. The rise of Christianity lead to a feeling of the games being wrong. Eventually the Emperor Honorius ended the Gladiatorial games after an Egyptian monk named Telemachus was killed after he plead to end the games. Honorius decreed the end of the games officially in 399 AD ushitory.org). Although the gladiator games were abolished at this time the last known gladiator fight in the city of Rome took place on January 1 404 AD ushitory.org). A bloodsport spectacle that once once brought emperors and nobles the people’s favor was now doing the opposite, and so it disappeared into history.

Emma- Colosseum

Originally called the Flavian Amphitheater, the Colosseum could hold between 50,000 and 80,000 people, probably averaging to about 65,000 spectators per event. It was used for about 500 years, and it is estimated that over 400,000 people died there. Construction began in 70 AD and it was finished in 10 years, followed by a 100 day streak of daily events to celebrate the emperor, the city, and the arena. Unlike other amphitheatres carved out of hillsides, the Colosseum is a freestanding concrete and stone structure. The land it was built on was originally a lake, so drains were built to clear the area, and the arena itself would have needed to have extensive architecture planning done before construction. Since its days of fame, the Colosseum has been used for several things, including a Christian shrine, a quarry, and a source for building materials. It was also partially destroyed by an earthquake in the 1300s. There were over 250 arenas built in this time, but this was the largest of them.

There were 76 entrance gates labeled with roman numerals, much how modern stadiums are set up. Spectators were packed in like sardines, and though some scholars guess that the people were sat according to their rank, more than likely everyone just packed in as tight as they could. The Colosseum was renovated a few times, and underground tunnels, sun and rain shades, and other amenities were installed. Some evidence of latrines and even water fountains has been found. Eventually canvas shades mounted on masts that extended from top of the arena were installed, which could be rolled out to protect spectators from the hot sun and sometimes rain. The floor of the arena was covered in sand to help absorb the spilt blood of combatants. The arena was used for the famous gladiator battles but also for chariot racing, naval battles, public executions, and even plays. There is no physical evidence that the naval battles happened, but there are a few ancient records that report the Colosseum being flooded and used to recreate famous battles at sea. Underground, there were tunnels, cages for animals, holding areas for upcoming gladiators, and machinery like trap doors. This underground area was probably not present during the supposed naval recreations.

Overall, the Colosseum was a hugely successful and impressive work of art that displays Rome’s power and position at the time. It was planned out carefully, and funds were controlled to ensure the best and fastest construction. Even over a thousand years past its last use, the Colosseum is still a huge attraction today, even if you now have to pay for tickets, and has been named one of the 7 Wonders of the World.

“Munera” The Games– Alaina

Before the games could begin, advertising had to be done to inform spectators of date, venue, editor, fighters, scheduled executions, and added perks for those in attendance; which may include information on food, drink, shade awnings, and on some occasions, “door prizes”. More detailed programs could be obtained the day of, and provided additional information about the matchups and fighting styles of the gladiators. The night before the event a banquet would be held as a sort of “last meal”. It was a chance for the gladiators to sort out their affairs as well as bring more publicity to the event.

The munera would begin with something similar to an “opening ceremonies”. A pompa, or procession, would enter the arena and led by lictors (who represented the power of the magistrate editor over life and death), and were then followed by trumpet fanfare, images of the gods (who were brought to “watch” the spectacle), a scribe, and men carrying in the palm branches to be awarded to winners. The magistrate editor would then enter with the weapons and armour to be used, and the gladiators entered last.

The exact order of the munera would differ among individual events, but would generally open with sham fights, which were fought with wooden or dummy weapons as a sort of warm-up. The munus could also be opened with animal spectacles, such as the ones Seneca praised involving trainers and handlers putting their heads in lions’ mouths or getting elephants to perform tricks like kneeling and walking on ropes. He also recalled wild animals fighting each other and people; with events in single combat being fought by bestiarii (beast-fighters), and groups of hunters demonstrating their skill in venationes, or “beast hunts”.

The next stage was called the ludi meridiani, which featured a wide range of possible content. It often featured the execution of noxii (condemned prisoners), which was sometimes done through fatal re-enactments of Greek or Roman myths. The audience, as well as the gladiators were not as enthralled with these events as they denied the noxii the dignity associated with a fair fight. Comedy fights, which had the potential to be lethal, would be performed in this stage of the munus as well.

By far the most popular event were the scheduled fights between gladiators. These were also the most expensive events, owing to the need for highly trained fighters who possessed both the skill in combat and showmanship needed to create a successful show. There were four main classes of gladiators: the Samnite (named for the warriors the Romans had defeated early on in the Republic) were the most heavily armored. They carried a sword or lance, a large shield, and wore armour on his sword arm and opposing leg. The second class were the Thracian gladiators, who carried a short curved sword called a sica and a small shield for deflecting blows.The Myrmillo gladiator (sometimes called “the fisherman”) was armed in a Gallic style and was easily idenfied by the crest in the shape of a fish on his helmet. The last class, the Retiarius, wore only a padded shoulder piece for armour and carried a heavy net and a trident.

In terms of the actual combat, retired gladiators often served as “referees”, and music was played during the match to enhance the experience. The match was over when a gladiator defeated his opponent, which was done when his opponent surrendered by raising a finger or was killed. The victor was awarded a palm branch, but a laurel crown and additional money from the audience could be awarded for an outstanding performance, and emancipation granted to those who fought an especially spectacular performance.

If a gladiator surrendered, it was up to the editor to determine whether he lived or not; a decision that was usually made based on the audience’s collective decision, and was marked by the infamous thumbs up or down gesture. In the later years of the munera, the audience favored missio (not killing the gladiator) for various reasons, some being the shortage of gladiators or the rise of Christianity and decrease in bloodthirst.

In the unfortunate event a gladiator was denied missio, he was killed by his opponent, usually by a well-placed blow to the neck, but that was only if he had already earned the right to a quick death, that is. If he died honorably (without begging for mercy or crying out), he would be removed to the morgue in a dignified manner, stripped of his armour, and his throat would be cut to ensure he was in fact dead. However, if he did not die with honor, his corpse would be subjected to a more humilating fate, which involved area officials dressed as Dis Pater, the god of the underworld, and Mercury who would beat the body with a mallet and “test” for signs of life with some sort of “heated wand”, respectively. The body would then be dragged out of the area and would be denied proper funeral rites and memorial; effectively condemning his manes (shade) to wander as a restless lemur forever.

Sources:

Cagniart, Pierre. “The Philosopher and the Gladiator.” The Classical World, vol. 93, no. 6, 2000, pp. 607–618. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/4352467.

Cartwright, Mark. “Roman Gladiator”. Ancient History Encyclopedia. Ancient History Encyclopedia, 3 May 2018. https://www.ancient.eu/gladiator/. Web. Accessed 22 October 2018.

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Gladiator”. Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc., 16 March 2018. https://www.britannica.com/sports/gladiator. Web. Accessed 22 October 2018.

Wikipedia contributors. “Gladiator.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 2 Oct. 2018. Web. 22 Oct. 2018.

Cartwright, Mark. “Roman Gladiator.” Ancient History Encyclopedia. 2018. https://www.ancient.eu/gladiator/

“Capua.” Livius.org. 2018. www.livius.org/articles/place/capua/

Talbert, Richard. Slootjes, Danielle. Brice, Lee. “Aspects of Ancient Institutions and Geography: Studies in HOnor of Richard J.A. Talbert” Impact of Empire: Roman Empire, C. 200 B.C.-A.D. 476. Volume 19. EBSCOhost. 2015. https://web-b-ebscohost-com.hal.weber.edu/ehost/detail/detail?vid=0&sid=27e32f3d-1548-4eea-85f8-3907f258fc29%40sessionmgr101&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%3d%3d#db=e025xna&AN=919102

The Ludus Originating

“About Rome.” BB Roma. 2012. http://www.bb-roma.com/en/blog/about-rome/ludus-magnus-the-gym-of-the-roman-gladiators.html

Coleman, Kathleen. “Gladiators: Heroes of the Roman Amphitheatre.” BBC- Ancient History in Depth: Gladiators. 2012. https://courseweb.hopkinsschools.org/pluginfile.php/130911/mod_resource/content/0/World_Studies/Gladiators.pdf

“Ludus Dacicus.” Wikipedia.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ludus_Dacicus

“Rome, Ludus Magnus.” Livius. http://www.livius.org/articles/place/rome/rome-photos/rome-ludus-magnus/?

“Gladiator Schools in Rome” http://www.tribunesandtriumphs.org/gladiators/gladiator-schools-in-rome.htm

ushistory.org. Ancient Civilizations Online Textbook. Gladiators, Chariots, and the Roman Games. Web. 21 10 2018 Accessed.

Thomassen, Lasse. “‘Gladiator,” Violence, and the Founding of a Republic.” PS: Political Science and Politics, vol. 42, no. 1, 2009, pp. 145–148. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/20452389.

Pierre Cagniart. “The Philosopher and the Gladiator.” The Classical World, vol. 93, no. 6, 2000, pp. 607–618. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/4352467.

Jackson, Ralph. “The Chester Gladiator Rediscovered.” Britannia, vol. 14, 1983, pp. 87–95. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/526342.

BOWER, BRUCE. “Roman Gladiator School Digitally Rebuilt.” Science News, vol. 185, no. 8, 2014, pp. 14–14. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/24366006.

History.com Editors. “Colosseum .” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 2009, www.history.com/topics/ancient-history/colosseum.

“Top Attractions.” Rome by CIVITATIS, www.rome.net/colosseum.

Hopkins, Keith. “History – The Colosseum: Emblem of Rome.” BBC, BBC, 22 Mar. 2011, www.bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/romans/colosseum_01.shtml.

Nikola Simonovski. “Ancient Romans Flooded the Colosseum to Re-Create Famous Naval Battles for Thousands to See.” The Vintage News, 13 Mar. 2018, www.thevintagenews.com/2018/03/13/colosseum-naval-battles-2/.

_Emrys_Wledig.jpg)

.jpg)