Weapons – scaleydragon

Weapons played a huge role in military, religious, and societal standing in the Legionary times in Rome. Arrowheads made or break armies, axes made to change fighting methods, spears had various symbolic meanings, and a weapon that started the evolution of all iron weapons. This weapon was the Styli (or pen).

Sagittae, or arrows, were excavated from Concordia and were well-preserved (Salvemini, Arrowheads 1228). These arrows were either triangular, flat, or quadrangular (Salvemini, Arrowheads 1229). Triangular arrowheads were designed to penetrate armor (Salvemini, Arrowheads, 1229). “The bladed heads once removed leave a flat slit of a wound, which the muscles surrounding the wound would help to close by automatically contracting. The more pronounced blades of the tri-lobed points would generate cuttings in three directions, plus a punch hole, causing the same reflex muscle action to hold the wound open. This would inhibit clotting, allowing blood to flow freely from the wound and make it much more open to infection (Salvemini, Arrowheads, 1229).” Flat arrowheads were designed to aid equestrian archer’s skills. They were usually fired from compact bows to fly straight (also aided from the arrowhead’s heavier weight) (Salvemini, Arrowheads, 1232). Quadrangular arrowheads were used to penetrate armored enemies in Legionary armies (Salvemini, Arrowheads, 1234). Although arrows and axes were the only weapons that didn’t have an impact on a Legionary’s status.

“> 3 SIDE BLADE ARROW HEAD < Very RARE Ancient Roman Legionary Archery Weapon • $34.98.” PicClick, 26 Aug. 2018, picclick.com/3-SIDE-BLADE-ARROW-HEAD-Very-123250213186.html#&gid=1&pid=1.

There are three types of axes, simple large axes with triangular hilts, simple axes with holed bottoms, and crescentic axes with a pike on the other side. Simple large axes were made to be heavy to deal sharp, blunt blows and the triangular hilts were used for better grip (Montanari 238-239). Simple axes with holed bottoms were made to be lighter to wield and easier to maneuver (also possibly used as projectile weapons) (Montanari 239-240). Finally, crescentic axes were made to deal significant blows with its crescent side. For the pickaxe side, it’s meant to pierce armor and pin enemies to the ground if needed (Montanari 240-241). The axes were used but not as popular as spears and swords.

Spears were popular due to being a symbolic weapon. It could represent nobility, righteous devotion to the church, and standing in the armies (Montanari 241-242). Most spears were in a lozenge shape and the spearhead metal and hilt of the spears would distinguish other Legionary statuses. The most important weapon during the Legionary time aside from the spear and sword would be the Styli.

IETE Journal of Education Binomial Sampling Charts Revisited with Graphical and Analytical Arguments – Scientific Figure on ResearchGate. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/The-lozenge-shape-confidence-belt-showing-reference-parameters-and-with-identifiable_fig3_275023546 [accessed 18 Oct, 2018]

Styli had a huge impact on weapon manufacturing and religious assemblies since they were used for creating maps, being used for mailing services, writing religious scripts, and more (Salvemini Styli 1.1). Most well-preserved Styli were made out of iron, it was speculated that crating Styli was a common practice to train blacksmithing skills (Salvemini Styli 1.2). When one could craft Stylis then they would move onto spears, arrowheads, swords, and axes. A Styli’s look could determine someone’s standing in an army, church, or in society (Salvemini Roman). The more gold or copper accents on the iron Styli body would mean higher class in a Legionary army and within churches.

Roman Funerals- Kimberlee Whitmore

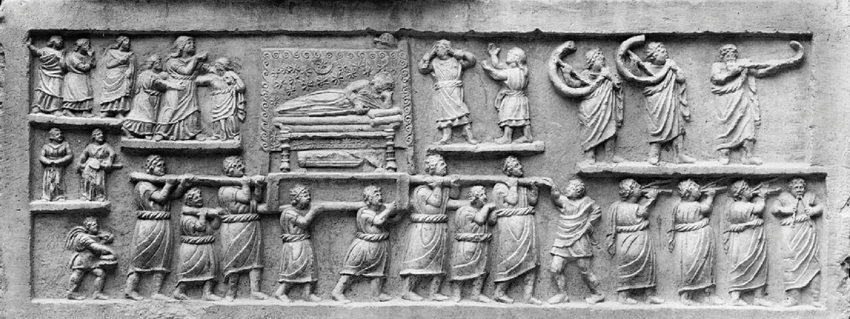

Funerals and burial, as in many cultures, were very important to the Romans. There were many rituals and events associated with a Roman funeral. Professional mourners were hired to comprise a large portion of the funeral procession; musicians, dancers and sometimes mimes who mimicked the dead or their ancestors were also hired (Sumi). The body, carried in a bier, would follow.

The end of the procession would have been the deceased’s family and friends, following behind the body. Funerals were very public, very loud events, and a great celebration. The more important you were the larger your funeral procession and the events surrounding it would be. The death of an emperor would result in a grand event for his funeral, there would be a parade though the center of the city and many eulogies and speeches would be delivered (Favro). The rituals of the funeral were performed to exactness, many believed that if they were not performed correctly the dead would have a difficult transition to the afterlife (Hope). Many of the records that remain about Roman funerals only describe the funerals of the very rich and may not accurately represent what the average funeral would have been like (Thompson).

Early in the Roman empire it was very common to cremate the body, inhumation, or burial, had become more common by the mid second century and predominant by the mid third century though the end of the Roman empire (Thompson). When the body was cremated it was taken to the necropolis and burned on a funeral pyre. Ashes and any remains, such as bone fragments and teeth, would be gathered and put into an urn and the urn would be buried. It was believed that until the body was contained within the urn the dead’s spirit had not yet crossed the River Styx and was still present (Fife). If the body was to be buried it would be placed in an intricately decorated sarcophagus before burial. An epitaph was often included on the urn or sarcophagus, this inscription would include the name of the deceased, their birth day and life span, their relations, political offices or military rankings they held and often some form of sentiment. After the cremation and/or burial of the body a feast would be held, it was a marker for the soul to move on to the afterlife and for their family to continue on without them (Fife).

Funerals in the military would have been similar to other Roman funerals, but likely not as lavish. The conditions they lived in could have made it difficult to perform the intricate ceremonies, the dead were highly honored, although their funerals were quite simple. If the funeral had to be carried out quickly after a battle the soldiers would be buried in a mass grave or given a mass cremation, this was always avoided if possible, so the dead could be honored separately. At permanent garrisons of the Empire a small portion of the soldiers’ pay was set aside for funeral expenses. Many of the cemeteries at these outposts had special areas set aside to build pyres that would be reused multiple times for different individuals (Thompson).

Roman funerals were events steeped in ritual and ceremony, members of high society would have lavish and very public funerals, while the funeral of a soldier was often much simpler and less celebratory.

Deities – Cassandra57

The Romans had many gods and goddesses which they worshiped. However, there were only a few main gods that had to do with warfare: Mars, Bellona, Honos, and Victoria. Roman military leaders and soldiers would honor these gods in order to be successful in battle. Each of these gods had a different role to play in warfare and each was essential to the Romans.

https://www.mygodpictures.com/victoria-crowning-mars/

Mars is the god of warfare, agriculture, and animal husbandry and was perhaps one of the most important gods to the Romans. He is said to have been the father of Romulus and Remus, who founded Rome (Scopacasa). Therefore, Mars was seen to be the protector of the Roman land (Scopacasa). Many of the rituals/celebrations which take place between March and October (the war season) can be traced back to the honoring of Mars. One interesting point about Mars is the fact that many of his legends include him appearing on the battlefield and fighting amongst the soldiers, “However, once set loose on the battlefield, Mars was considered capable of indiscriminate destruction” (Scopacasa). Mars was also so important that a typical sacrifice to him consisted of a bull, ram, and a boar all at once (Scopacasa). Mars was important in warfare because he was able to rally the troops and bring enough bravery and spirit of war in order to succeed in battle (Scopacasa).

Bellona is the Roman goddess of war, and her role was mostly associated with foreign warfare. In literature, her symbols typically include a shield, a spear, a torch, and a trumpet (Holland). Her temple is located outside the city of Rome, and this is where the senators would meet in order to discuss or declare war on foreign nations (Holland). When Rome would declare war on another land, it became a ritual to cast a spear from Roman land to outside the city in the direction of the land they were declaring war on. However, when that land was simply too far away, the spear would be cast in front of Bellona’s temple because it was seen to represent all foreign lands (“Fetial”). Bellona was important because she helped the Roman troops while they were fighting abroad.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bellona_(goddess)

Honos is the Roman god of chivarly, honor, and military justice. He was also commonly associated with the god, Virtus, who represented bravery and military strength. Honos is typically depicted with a cornucopia and a branch or sceptor (Dowling). He would have been important to the Romans during times of war because they wanted to be worthy of the spoils in which they gained. The Romans also were concerned about whether a war was righteous or not (“Fetial”). Therefore, adhering and praying to Honos would be seen as a way to keep their fight just.

Victoria became a prominent goddess because of her ability to determine the victor in battles (“Victoria”). She became the personification of victory and was often depicted with wings like the Greek goddess Nike (Thornton). Successful generals would worship her as they returned to Rome (“Victoria”). It is obvious as to why she was seen as important to the Romans since she could determine who was the victor over life and death (“Victoria”). Her importance can also be seen by the multiple temples dedicated to her, the most important being the one on Palatine Hill (Thornton). She even has a golden statue in one of the temples dedicated to Jupiter, the head god to the Romans (Thornton). Prayers and sacrifices to Victoria would help lead to victory on the battlefield.

Important Military Festivals and Holidays- Halle

In the Roman calendar the new year starts in March. This is so that the years can start with the Campaign season. While there are many significant festivals throughout the year, I will only be focusing on those during the military season, March through October, and those immediately related to them.

Martius (March) 1st is the birthday of Mars for whom the month is named. It is also a celebration of a battle early in Rome’s history wherein wives and children kept their soldiers from walking into a trap. The war was won when the king, here unnamed, sacrificed a bull to the God Jupiter. Phoebus dropped a shield (2) from the sky to trick Rome’s opponents (Ovid). The 9th is the festival of sacred shields, also called the dancing of the shields after the dancing priests of Mars, the shield given to the Roman King on the battle of Martius, and the original eleven replicas made to conceal its identity, are taken out to hearten the people and the army. It was also believed to be a way for the army to have good luck in the upcoming campaign season (Warde, 44). There is an account where the shield that fell from the sky was replaced by a replica, and that campaign season was a disaster (Warde, 46). The 14th is the second of the Equirria, chariot racing and discus throwing dedicated to Mars (Ovid). The 17th of march is a celebration of Jupiter userping Saturn, this is symbolic of Rome dethroning its enemies. 23- The purifying of trumpets and a sacrifice to “the Strong God” (Ovid). The 23rd and the 24th are also for the Purification of the Trumpets, most likely tubas, which were primarily used in the military (Warde, 64).

Capitoline Museums. “Colossal statue of Mars Ultor also known as Pyrrhus – Inv. Scu 58.” Capitolini.information.

A recreation of a Roman sculpture of the war god Mars, for whom the month of Marius, now March, was named.

April the 21st is a historical festival where the Vestal Virgins cleanse the city and the citizens. It was also a day to honor Romulus, the founder of Rome, for blessing the walls of Rome to never fall (Ovid). There are many rites involved with the Founding celebration including: repeating the prayer four times, and jumping over a flame three times. Similar celebration similar to this are found all over Europe, probably due to the spread of the traditions via the army (Warde, 83).

October 15th (ides) is the date of an ancient horse sacrifice to Mars. The origin and reason for this sacrifice is unclear, it is hypothesized that the winning horses from the Equirria, or perhaps the best war horses from the campaign season, were sacrificed to Mars. This was likely done as a thank you to Mars (Warde, 242). This sacrifice marks the end of military campaign season (Ovid). The literal sacrifice is phased out by the start of the republic, though the celebration stays (Warde, 242). The 19th is a ritual cleaning and storage of weapons for winter dedicated to Mars. This sacred cleansing was known as Armilustrium, there is evidence that the sacred shields make a second appearance (Warde, 250).

Ancient shield illustration from Nordisk familjebok

A depiction of the sacred shield bequeathed to the king by the Gods.

Februarius (February) 27th is Equirria, first of two horse racing festivals to Mars, Ovid claims this festival to be based on the chariot runs that Mars himself made (Ovid). “The Equirria occurred between King’s Flight and New Year, bridging the period of ‘disorder’: held immediately before the new moon, they prepared the way for the reestablishment of order with the new month and year (Rüpke)”

Works Cited

“> 3 SIDE BLADE ARROW HEAD < Very RARE Ancient Roman Legionary Archery Weapon • $34.98.” PicClick, 26 Aug. 2018, picclick.com/3-SIDE-BLADE-ARROW-HEAD-Very-123250213186.html#&gid=1&pid=1.

IETE Journal of Education Binomial Sampling Charts Revisited with Graphical and Analytical Arguments – Scientific Figure on ResearchGate. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/The-lozenge-shape-confidence-belt-showing-reference-parameters-and-with-identifiable_fig3_275023546 [accessed 18 Oct, 2018]

Montanari, Daria. “Early Bronze Age Levantine Metal Weapons from the Collection of the Palestine Exploration Fund.” Palestine Exploration Quarterly, vol. 150, no. 3, Sept. 2018, pp. 236–252. EBSCOhost, doi:10.1080/00310328.2018.1491937.

Salvemini, Filomena, et al. “Morphological Reconstruction of Roman <italic>styli</Italic> from <italic>Iulia Concordia</Italic>—Italy.” Archaeological & Anthropological Sciences, vol. 10, no. 4, June 2018, pp. 781–794. EBSCOhost, doi:10.1007/s12520-016-0390-4.

Salvemini, Filomena, et al. “Morphological Reconstruction of Roman Arrowheads from Iulia Concordia: Italy.” Applied Physics A: Materials Science & Processing, vol. 117, no. 3, Nov. 2014, pp. 1227–1240. EBSCOhost, doi:10.1007/s00339-014-8511-3.

Salvemini, Filomena, et al. “Residual Strain Mapping of Roman Styli from Iulia Concordia, Italy.” Materials Characterization, vol. 91, May 2014, pp. 58–64. EBSCOhost, doi:10.1016/j.matchar.2014.02.008.

Favro, Diane, and Christopher Johanson. “Death in Motion: Funeral Processions in the Roman Forum.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, vol. 69, no. 1, 2010, pp. 12–37. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/jsah.2010.69.1.12.

Fife, Steven. “The Roman Funeral.” Ancient History Encyclopedia, Ancient History Encyclopedia, 18 Jan. 2012, http://www.ancient.eu/article/96/the-roman-funeral/.

Hope, Valerie M., and Janet Huskinson. Memory and Mourning : Studies on Roman Death. Oxbow Books, 2011. EBSCOhost, hal.weber.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=570000&site=ehost-live.

Sumi, Geoffrey S. “Impersonating the Dead: Mimes at Roman Funerals.” Oral History Review, Oxford University Press, 15 Jan. 2003, muse.jhu.edu/article/37888.

Thompson, T.j.u., et al. “Death on the Frontier: Military Cremation Practices in the North of Roman Britain.” Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, vol. 10, 2016, pp. 828–836., doi:10.1016/j.jasrep.2016.05.020.

Dowling, Melissa Barden. “Honos.” onlinelibrary-wiley.com.hal.weber.edu, Wiley Online Library, 26 Oct. 2012, DOI: 10.1002/9781444338386.wbeah17204. Accessed on 21 Oct. 2018.

“Fetial.” Encyclopedia Britannica, the Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica, Encyclopedia Britannica Inc., 24 Feb. 2016, www.britannica.com/topic/fetial. Accessed on 21 Oct. 2018.

Holland, Lora L. “Bellona.” onlinelibrary-wiley-com.hal.weber.edu, Wiley Online Library, 26 Oct. 2012, DOI: 10.1002/9781444338386.wbeah17071. Accessed on 21 Oct. 2018.

Scopacasa, Rafael. “Mars.” onlinelibrary-wiley-com.hal.weber.edu, Wiley Online Library, 26 Oct. 2012, DOI: 10.1002/978144433836.wbeah17258.

“Victoria.” talesbeyondbelief.com, http://www.talesbeyondbelief.com/roman-gods/victoria.htm. Accessed on 21 Oct. 2018.

Ovid. Fasti. Translated by Frazer, James George. Loeb Classical Library Volume. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1931.

Warde, W. The Roman festivals of the period of the Republic, 1847-1921. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015004760644

Capitoline Museums. “Colossal statue of Mars Ultor also known as Pyrrhus – Inv. Scu 58.” Capitolini.information.

![Achaemenid [Converted]](https://legioilynx.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/the_achaemenid_empire_at_its_greatest_extent.jpg?w=500)