Preston Hodson, Troy Esquibel, Josiah Oldham and Nathan Blue

10/11/16

Introduction (Time, Place and Troops): Preston Hodson

It’s the year 327 b.c. After years of struggles I’ve finally conquered the Persians! Some say that this should be sufficient, that I should enjoy the victory and be content, but not me. I crave a challenge, and I won’t be stopped. This time I’ve set my sights on India. We’ve crossed the Hindu Kush and invaded Kabul, as well as Swat. My army is, as my name states, nothing short of great. With my force of nearly 90,000, comprised of mostly Macedonian and Persian soldiers, along with some Greek cavalry and other Balkan allies, we’ve had great success. As many of them have been with me since the beginning of my conquests, they’re getting to be pretty old. It’s now necessary for me to leave them behind as garrison troops and guards in each of the cities that we conquer, that way they won’t take up valuable provisions from my younger, healthier troops, and at the same time they can at least somewhat enjoy the rest of their lives in peace. As we lose soldiers it’s proven rather difficult to acquire new ones. We have garnered a few here and there as we conquer cities and villages, but not sufficient. We’ve also asked for reinforcements from the homeland, but with minimal results. All in all, our situation isn’t too bleak to be quite honest, we’re having a lot of success. I just hope my burning desire to conquer more territory doesn’t cause my troops to revolt and turn against me, that would throw a nasty kink in my plans for world conquest… But hey, it’s not like that would ever happen, right? On we go to Porus! To India, and beyond!

Supply Logistics: Troy Esquibel

Philip, before Alexander, revolutionized the speed and agility of a massive army, breaking with Greek tradition on several fronts. The Macedonian members of the Phalanx were typically too poor to invest in heavy armor or Hoplite equipment, and as a consequence they’re personal effects were able to be transported, for the most part, on their person. This had the effect of reducing the amount of members needed in a baggage train and also reduced the reliance on pack animals. As a result, the need for grain, water, and other supplies was greatly reduced, and as the army was able to march over vast distances more swiftly, it also reduced the amount of provisions they would need from location to location.

The minimum amount of grain to satisfy a Macedonian soldier was 3 pounds and the minimum amount of water needed was 2 quarts (Engels p. 9). These are bare minimum quantities, and it is assumed, most prominently in Engels—verified by modern military experiments—that an army could only possibly march through desert conditions with 4 days’ worth of supplies. Alexander dealt with this problem in several ways, one of them was by marching along rivers, that way provisions could be delivered by watercraft as opposed to beasts of burden. Secondly, by ordering quickened and double timed marches out of problem areas, such as deserts, thus conserving rations and escaping problem areas more quickly. Thirdly, this was combated was by making allies out of his enemies, frequently before there was any chance of combat, and using the new partnerships of his allies to have outposts laden with supplies ready for his troops before they arrived (Van Mieghem p. 42).

Another important factor, alluded to by Engels, was the agricultural prowess of ancient peoples. The desert areas that Alexander had marched through were vastly more productive than contemporary times, referring to “the Negev Desert and the Tigris—Euphrates Valley. the respective yield rate was five times and twenty times higher than today, and the extent of the cultivated area was about ten times greater” (Engels p. 8). This meant that whatever amount of supplies Alexander did not bring, he was able to forage, steal, or barter for amongst local peoples. Many times those cities he conquered forfeited supplies for the campaign. Alexander was also careful to march during the harvest season to maximize efficiency (Engels p. 9).

Baggage Train and Local Encounters: Josiah Oldham

The baggage train is just as important as the army itself. Alexander could not depend on his soldiers to carry all the war equipment and siege devices by themselves, but he also couldn’t afford to bring an over-abundance of staff and items. This was, after all, a very long journey, and carrying enough food is a must (needless to say). While his soldiers often brought their own personal effects, as previously mentioned, he needed servants or pack animals to lug along the food and water. Pack animals, though, likely outnumbered the human servants. In an emergency without rations, only one of those options is edible. With careful budgeting and planning, Alexander can get away with bringing less food than the army needs, gambling on contributions from smaller towns along the march. Conversely, it is also important to bring plenty of extra weapons and armament- explained further when dealing with locals.

On this campaign, speed is of the utmost importance. While they need to keep critical personnel such as doctors and veterinarians, and guards for the siege equipment, other people just slow the trail down. These include the merchants, philosophers and poets, as well as secretaries and soldiers’ families. The veterans are also assets, as detailed in the following paragraph.

On the way to India, as is explained in the Route section, the river paths dictate that the army will encounter several small towns. They severely outnumber anyone in these towns, and as such threats of force are serious. He can station veterans and contingents of soldiers from the train in these towns, armed well enough to prevent rebellion. After the new government is in place, and the train takes supplies from them, they are several mouths fewer and several pounds of supply richer. In other words, the more towns they conquer, the easier and faster the march becomes.

However, there is one important note: as tempting as it seems, looting these towns for anything but supplies is not a good idea. Better to wait for higher-value targets than to slow the army and train down with dead weight.

Route: Nathan Blue

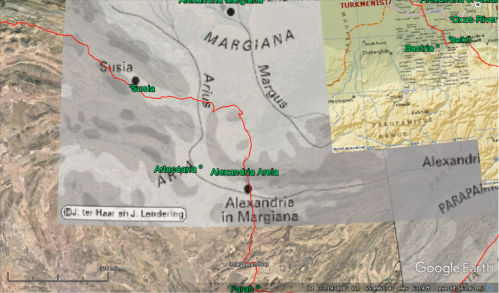

Alexander the Great would have been in a bind to get his men from location to location without wasting supplies or time on the march to India. There would have been a constant press to make sure that the soldiers had the proper food and water between towns and cities. An important factor on getting to each city would be simple to ask the locals the best route to the next place to stop. Many times these routes follow rivers, and the invasion path occasionally crosses them when necessary. The crossing of the Arius River from Susia to Alexandria Areia is a good example. Battles won would have also allowed for captured enemies to be brought along and provide on the trail instructions.

Accuracy of Information: Troy Esquibel

Like a lot of ancient history, most of this information is the best approximation of the logistical and supply chain strategies of Alexander during the duration of his campaign. There are many extant sources, but all of these were written centuries after the actual campaign. The most trusted of these sources was Arian, from the first and second century current era, but even he relied heavily on Ptolemy, who existed several centuries after Alexander. Engels suggests that Ptolemy is the most reliable, and gives proof to geographical and fossil records that still prove to be extremely accurate today. Like all ancient history, we can only give our best approximation of the facts.

Works Cited

Lendering, Jona. “Alexander the Great.” Livius.org. Livius.org, 30 Jul. 2016. Web. 8 Oct. 2016. (http://www.livius.org/articles/person/alexander-the-great/)

Arrian trans. Chinnock, E.J. “The Anabasis of Alexander.” The Selwood Printing Works, 1884.

Van Mieghem, Timothy. “Logistic Lessons From Alexander the Great.” Quality Progress January 1998. P 41-46, Web

Engels, Donald. Alexander the Great and the Logistics of the Macedonian Army. University of California Press, 1978.

Google Earth Version 6.2 (12/31/1969) Iran (Susia). Lat 35.99N Lon 60.01E, 2299 ft. Eye alt. 563.82 mi. Places Layers Alexander’s Route Out. Digital Globe http://www.google.com/earth/index.html (Accessed October 5, 2016).