Types of bows

Introduction

Archery is simple in concept, yet it represents an extremely sophisticated technology. In its most basic form, a bow is a piece of wood slightly bent and held in tension by a connecting bowstring. However, as the bow is drawn, tensile stress increases along the back or outside curve simultaneously with compressive forces developing along the inside curve or belly. (Knecht) The bow stored the force of the archer’s draw as potential energy, then transferred it to the bowstring as kinetic energy, imparting speed and killing power to the arrow.

Advantages and Construction

Like its namesake, the composite bow combines different materials (wood, sinew, and horn) and utilizes them fully, creating a mechanical tour de force. Specifically, the sinew on the back handles tensile stress, while the horn on the belly has 3.5 times more compressive strength than wood (Knecht). It starts with a wooden core of maple, poplar, or ash. The core can be any type of wood, so long as glue can stick to it easily, it is flexible and bends easily, and has a straight grain, to avoid twisting of the limbs(Knecht). The core is thin, acting more like a spacer and surface to which the horn and sinew was attached. Its thinness also reduced the overall weight of the bow. Composites are made of multiple pieces, each joined with animal glue in V-splices to allow for the sharp bends that many recurve bows require. Water buffalo horn is the most common, although gemsbok, oryx, ibex and Hungarian grey cattle horns are also used (Wikipedia Contributors). Sinew, generally the Achilles tendon or back tendons of wild deer, is soaked in glue and applied in layers on the back of the bow. After attaching the sinew, the bow was placed in a cool, dry location to allow the glue to set. After six months or more of drying, the bowyer slowly bends the bow into its final shape, adjusting to make sure the limbs will draw evenly . Finally, a waterproof covering of thin leather, bark, or snakeskin is added. Scythian and early sarmatian bows were short at 3 ft, the handle set back and the limbs curving with slightly curled ends, middle to late sarmatian and hunnic weapons were longer at 5 ft (De Souza).

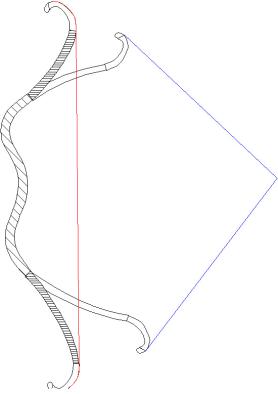

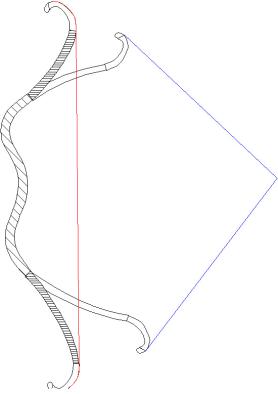

Unstrung, strung, and drawn composite bow & Cut out diagram of construction materials

A bow can store no more energy than the archer is capable of producing in a single movement of the muscles of his/her back and arms, but the composite recurve released the stored energy at a higher velocity, thus overcoming the arm’s inherent limitations (Encyclopedia Britannica). Longbows are bigger, heavier, and shoot at a lower velocity. Composites not only shoot with greater velocity, they are much smaller and lighter, making them perfect for horseback archery. A prime advantage of the composite bow was that it could be engineered to essentially any desired strength, the bowyer being able to produce a bow capable of shooting light arrows at long range, or maximize penetrative power of heavy arrows. (Encyclopedia Britannica) Composites are mechanically superior to wooden bows as the horn and sinew made it capable of standing greater compression while maintaining more elasticity. The steppe bow could transfer most of its energy to the arrow, thus allowing it to shoot farther than a bow of equal draw weight, a typical cast being 300 meters (Szabó).The more powerful composite bows, being very highly stressed, reversed their curvature into a complete ‘C’ shape when unstrung. They acquired the name recurved since the outer arms of the bow curved away from the archer when the bow was strung, imparting yet another mechanical advantage at the end of the draw.

Historical Context

The composite bow appears to have developed in separate regions but at roughly the same time, in cultures in Mesopotamia, Anatolia, and the Eurasian Steppes. The earliest surviving examples of composite bow is western Asian angular bow that appeared during 3rd Millennium BC. (Knecht)

Akkadian Stele from the 3rd Millennia BC. Depicts composite bows utilized by army of Sargon of Akkad

In 1992, from among the Egyptian artifacts in Tutankhamun’s Tomb, Howard Carter recovered 32 angular composite bows along with arrows, quivers, and bow cases (Knecht). These bows are an earlier form that made a shallower angle and had shallower recurve limbs. Replicas of these suggest that the angular composite bow provided Egyptian archers with a smooth accurate and high powered shot. The short length of these bows made them lightweight and maneuverable, highly suited for chariot-borne archers. (Knecht)The introduction of composite bow, stronger and more effective than the simple bow, was part of a striking change in military technology at the beginning of the Pharaonic New Kingdom. This modernization was to keep pace with the military innovations of neighboring countries and prevent any recurrence of a foreign incursion like that of the Hykso, who had possession of composites, in the second intermediate period (1650-1550bc). (Knecht)(Wikipedia Contributors)

The most prominent form of composite bow is a design referred to as the Scythian bow, known to the Romans as Sythicus Arcus. (Knecht) Its form became fully developed under the Cimmerians by the 9th century BC. The Scythians, originally from Iran (De Souza) moved into the Pontic Steppe north of the Black Sea in the 8th Century BC. Records from 700 BC onward mention composite bows being used by the Cimmerians and Scythians, who attacked the kingdom of Urartu and ravaged the Anatolian kingdoms of Lydia and Phrygia (Szabó). In the next century, they raided Assyria, Damascus, Phoenicia and Israel, up to the Egyptian border. The prophet Jeremiah wrote: “At the sound of horsemen and archers, every town takes to flight.”( Szabó) It is impossible to discuss recurve composite bows without recognizing the equestrian cultures that developed them. Eurasia is a series of connected regions of flat, grassland steppe. As mentioned by Herodotus, “they [the Scythians] are all mounted archers who carry their homes along with them and derive their sustenance not from cultivated fields but from their herds…their land and their rivers support this way of life.” The land there is perfect for grazing animals like horses and cattle, leading the cultures there to develop around that. Steppe nomads excelled in horse husbandry and horseback riding, developing equestrian culture of decorated saddlery and harness, herding tools and clothing fashions. Characteristic also of the black sea hinterland and the lands down to northern Greece are finds of gold sheet covers for bow case and quiver combinations, called gorytoi. These demonstrate that the bow was carried strung on the horse archer’s left side. (De Souza)

Scythian bow artifacts

Diagram of drawn Scythian bow

For other goods not provided by their herds, like grain, textiles, and metalwork, nomads traded with their sedentary neighbors. They could also just take things by force. Horse archers could shoot their bows in a near 360 degree arc from a fast moving platform. This meant that mounted-archer warfare was mobile and fluid, operating in a cloud of riders, concentrating on specific targets and then wheeling away out of reach when threatened (De Souza). Shooting was rapid and at close range to defeat armor. All horse archers could shoot backwards as they withdrew in a ‘Parthian shot’. The appearance of nomad hordes often bewilderingly sudden and unexpected. The mobility of horse archer groups meant they could range widely in short time and numbers difficult to estimate accurately. Nomads could also campaign much more effectively than sedentarists in winter, when steppe horses could forage in deep snow, and summer obstacles such as rivers and marshes were frozen over. (De Souza)

In 513 BC, King Darius I of Persia invaded Scythia. The Scythians sent their women and children to a safe place and simply let the Persians chase them all over the steppe. Their strategy was to exhaust and harass the Persians with archery and cut them off from supplies(Szabó). They laid waste to the countryside, so the Persians would be unable to forage. Darius withdrew, and Persia was never able to conquer Scythia.

Recurve bows depicted on the walls of the Palace at Susa

From images on the walls of Darius’ palace at Susa, it is likely that the Persians adopted the composite bow from their encounter with the Scythians. During the Greek invasion, at Plataea, “the [Persian] horsemen rode out and attacked, inflicting injuries on the entire Greek army with their javelins and arrows, for they were mounted archers and it was impossible for the Hellenes to close with them” (Herodotus).

Alexander the Great was one of the only commanders who successfully defeated a mounted archer army on his first try. In 328 BC, Alexander battled with Saka and Massageta nomads at Syr Darya, on the very edge of the nomad’s arid steppe (Szabó). It was the first ever defeat of nomadic cavalry by settled agriculturalists, but it was close. Of the 4500 nomadic horsemen, only 800 were dead. Having sustained a considerable loss already, Alexander wisely chose not to follow them into their own lands.

Parthian Shot Coin. Mounted archery shot in which the rider turns in the saddle and shoots backward. Made famous by references to Parthians, but really, any skilled horse archer could do it

“They are really formidable in warfare….. the Parthians make no use of a shield, but their forces consist of mounted archers and lancers, mostly in full armour. Their infantry is small, made up of the weaker men; but even these are all archers. The land, being for the most part level, is excellent for raising horses and very suitable for riding about on horseback; at any rate, even in war they lead about whole droves of horses, so that they can use different ones at different times, can ride up suddenly from a distance and also retire to a distance speedily.” Cassius Dio on 3rd century ad Partho-Sasanians

The Battle of Carrhae in 53 BC pitted sixteen thousand Parthian horsemen against twenty-four thousand Roman soldiers. (Szabó) The highly disciplined army under Marcus Licinius Crassus and his grown son would find the combination of mobility and archery to be deadly. Plutarch wrote of the Parthians: “Their bows were large and strong, yet capable of bending till the arrows were drawn to the head; the force they went with was consequently very great, and the wounds they gave, mortal.” The Parthians pretended to retreat, drawing out the forces of the younger Crassus far from the main army and turning back on them. The Parthian heavy lancers defeated the Roman cavalry, while Crassus’ infantrymen withdrew to a hill, where they were shot to pieces. Ultimately both the elder Crassus and his son were killed and the army surrendered (Szabó).

The Romans, like the Persians, also picked up on composite design, which became the standard weapon of Roman Imperial archers. The stiffening laths (also called siyah in Arabic/Asian bows and szarv in Hungarian bows) used to form the actual recurved ends have been found on Roman sites throughout the Empire, as far north as Bar Hill on the Antonine Wall in Scotland (Wikipedia Contributors).

The late Roman Empire was dominated and terrorized by Attila the Hun and his armies. The Huns swept up a mass of peoples, inc. other steppe nomads during their movement west into Europe. Writers such as Ammianus Marcellinus, Olympiodorus, and Procopius acknowledged the Huns to be the world’s best archers. (Szabó) The Hunnic bow, also a composite recurve, was the technical secret to their vast success (Man).The Huns lengthened and stiffened the recurved ends called siyah or ears, of their bows and set them at sharply recurved angles. Increasing overall energy storage and creating a higher initial draw weight, these alterations allowed a heavier arrow to be shot more efficiently (Knecht).

If it wasn’t enough to have the Huns, the Byzantine Empire was also attacked by an alliance of Magyars and Pechenegs in 934 AD. In an unnamed battle on the Balkans, the Magyar and Pecheneg horsmen revolved around them ‘like a mill wheel’, and when the Byzantine cavalry rushed forward, gave a murderous volley of arrows from either side, followed by a sword charge (Szabó). The defeated Byzantines surrendered and paid tribute for years.

Throughout the Middle Ages, composite recurves were generally used in more arid countries; the all wooden longbow was the norm for more humid regions, like Great Britain. Composite recurve bows and mounted archery continued to be important in battles right up until the widespread use of firearms and gunpowder. Even still, the composite bow and archery flourishes today as an athletic sporting event.

A modern horse archer at competition

Works Cited

Herodotus. The Landmark Herodotus: the histories. New York: Pantheon Books, 2007. Print

Knecht, Heidi ed. Projectile Technology. New York: Plenum Press, 1997. Print

De Souza, Philip. The Ancient World at War. New York: Thames & Hudson Ltd. 2008. Print

De Waele, An. “ Composite bowat ed-Dur (Umm al-Qaiwain, U.A.E.)” Arabian Archaeology & Epigraphy. Nov 2005, Vol. 16 Issue 2, p154-160. Web. 18 Apr. 2012.

Man, John. “Centaur of Attention”. History Today; Apr2005, Vol. 55 Issue 4, p62-63. Web. 18 Apr. 2012.

Szabó, Christopher. “The composite bow was the high-tech weapon of the Asian steppes”. Military History; Dec2005, Vol. 22 Issue 9, p12-22. Web. 18 Apr. 2012.

“Composite Bow.” Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2012. Web. 18 Apr. 2012. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/130082/composite-bow.

Wikipedia contributors. “Composite bow.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 14 Mar. 2012. Web. 17 Apr. 2012.

Wikipedia contributors. “Bow shape.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 30 Mar. 2012. Web. 16 Apr. 2012.